The food-security dilemma in northern Indigenous communities in Canada, and the disproportionately high incidence of dietary-related disease, remains a distressing reality with few prospects of recovery. A research study led by Dr Michael Robidoux from the University of Ottawa responds by presenting a novel, multidisciplinary approach based on first-hand experiences working with First Nations community members in a remote subarctic region of northern Ontario. The methods and analysis used by them provide a repeatable model for evaluating land-based foods to determine their potential contribution to food security.

Although Canada is a resource-rich country that consistently rates among the best in the world in most economic and quality-of-life categories, approximately half of all Indigenous households in the country are food insecure. This incidence can reach 70% in northern Ontario, where most meals are nutritionally deficient due to limited access to, and excessive costs of, healthy food options. These dismal figures are especially concerning because they are significantly higher than the national average for food insecurity (8.3%).

Photo Credit: DarrenBaker, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

There have been a lot of studies and community-based initiatives in response to the disproportionate rates of food insecurity and the health problems that come with it. Despite these efforts, food security issues persist due to their logistical complexity and the need for long-term systemic reform to have real and long-lasting effects. The historical and contemporary roots of these disparities are systemically informed by a lengthy history of colonialism and capitalism dating back to the 17th century.

“Forced settlements imposed by government legislation and treaty signings have shattered the semi-nomadic lifestyles that once allowed Indigenous peoples to live off the land.”

Apart from the high cost of market food and limited availability of nutritious foods, a lack of government assistance for nutritious-food programmes exacerbates food insecurity. The Canadian government is responding by drafting a ‘National Food Policy’ and modifying the existing Nutrition North programme, among other things. Indigenous groups, academics, and food-policy advocates have repeatedly urged the federal government to encourage traditional food harvesting, not only as a means of alleviating food insecurity and the high rate of dietary-related disorders, but also as a means of restoring local food systems. While a ‘$15 million over five years’ investment as part of the Nutrition North programme appears admirable, the impact of local food harvesting on improving food security has yet to be determined.

A novel multidisciplinary approach

A research study led by Dr Michael Robidoux from the University of Ottawa responds by presenting a novel multidisciplinary approach based on first-hand experiences working with First Nations community members in a remote subarctic region of northern Ontario. The team comprises of Dr Robidoux (an ethnologist and professor), Derek Winnepetonga (a hunter and trapper), Dr Sylvia Santosa (Canada Research Chair in Clinical Nutrition), and Dr François Haman (a biologist).

The study estimates the community’s total food requirement and the amount of wild animal food sources required to sustain yearly food intake – known as the transferrable energy demand approach. Policymakers will need to use this approach to put the amount of wild food needed in context, to enhance food security rates and, as a result, dietary-related disorders. It is based on a community-based participatory research design that the Indigenous Health Research Group (IHRG) has used in research with various Indigenous communities in northern Canada for the past decade. This sort of research is extremely conducive to the development of policy that benefits individuals and communities since it better reflects their needs and experiences, in addition to encouraging action-oriented conclusions.

Dr Robidoux conducted his research during peak hunting seasons.

Understanding the community of Wapakeka

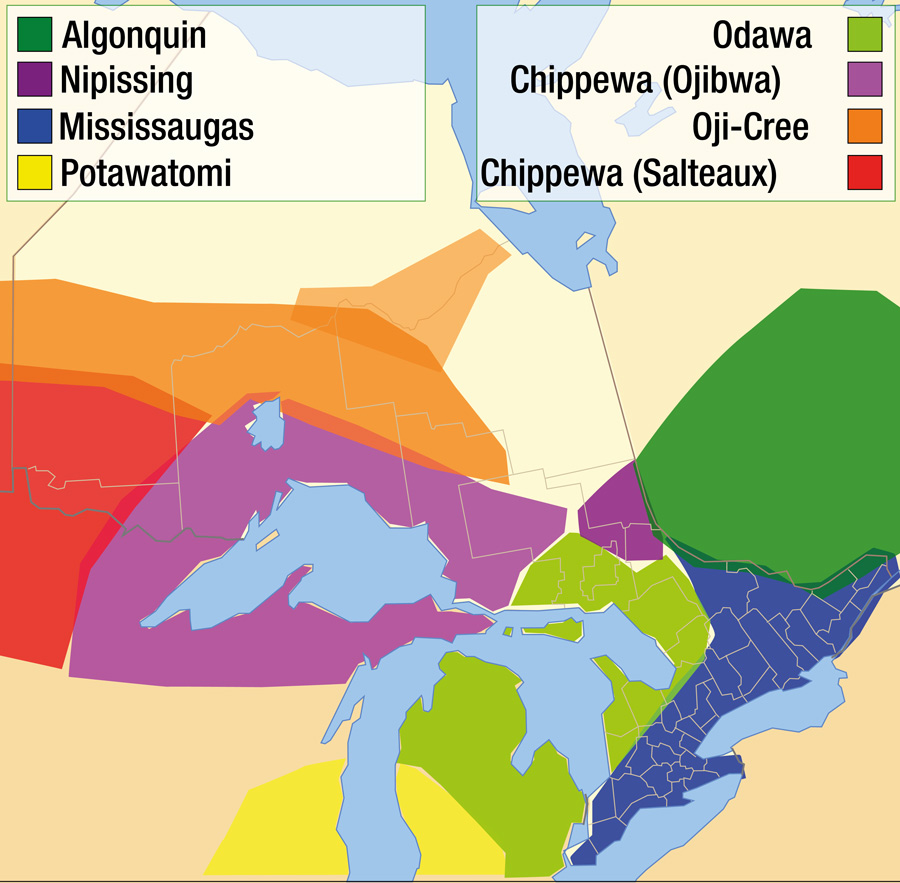

Wapekeka First Nation (Angling Lake) is an Oji-Cree community located 451km north-east of Sioux Lookout in Ontario’s subarctic region. Forced settlements imposed by government legislation and treaty signings have shattered the semi-nomadic lifestyles that once allowed Indigenous peoples in this region of Canada to live off the land. Larger populations concentrated in specific areas have resulted in the depletion of wild food sources in the immediate area, forcing food harvesters to travel greater distances on the less-travelled territory to feed their families. While technological advancements such as snowmobiles, outboard motors, planes, and helicopters have made long-distance travel possible, the costs of the technology, as well as the costs of maintaining and operating it, have made land access unaffordable for an increasing number of Indigenous peoples. As a result, northern Indigenous peoples are left with two main food systems: one that draws from the land and the other that relies on imported store-bought foods. Unfortunately, these two food systems are failing to provide fundamental nutritional needs, leaving poor-quality processed foods as the primary source of nourishment, contributing to the obesity and type 2 diabetes epidemics in many communities.

Robidoux’s group has been doing ethnographic research in this region since 2006, studying local dietary practices. In Wapekeka, as in most other communities in this region, the diet is made up of a mix of market food and food collected from the land. The ethnographic work was mostly done during peak hunting seasons, with researchers living in the community for four- to six-week periods and participating in community activities such as hunting and fishing, food preparation (butchering, cleaning, and cooking), community feasts, community cookouts, memorial feasts, and informal meals.

At all times, detailed field notes and video documentation were kept. They included details of the types and quantities of food gathered and consumed, the method in which they were cooked, who participated in the activities, their frequency, and relative importance in each setting. This participatory–observational component of the study was (and continues to be) crucial in understanding the intricacies of eating behaviours, including both locally sourced and store-bought goods. According to the data obtained by Robidoux and other researchers, traditional food access is not equally experienced among community members in this region and throughout several Indigenous communities in Canada. This is due to a variety of social, economic, and life-situation factors. The food sources in Wapekeka are similar to what was obtained traditionally, although dietary choices have affected what is harvested most frequently.

“The methods and analysis used here provide a repeatable model for evaluating land-based foods to determine their potential contribution to food security.”

The outcome of the study

Understanding the potential impact of local food procurement in helping remote Indigenous communities address food security issues is critical, but requires accurate estimates of local food availability. The study presents estimates of the community’s total energy and macronutrient needs. Field research reveals that obtaining accurate data on wild animals harvested by hunters/gatherers by recalls or daily records takes a lot of time and effort, and the results are unreliable.

Using a different method of predicting harvest yields, the researchers calculated that a tiny subarctic First Nation village (population 500) would need 272 Gcal per year to support a sedentary lifestyle needing 8,660kg of protein at 15% Total Energy Expenditure (TEE). Hunters in this community confirmed that harvesting levels are meeting 56.7% of average protein requirements, or 8.5% of total (sedentary) energy requirements, based on these numbers of animals (38,816 kg of wild food). These findings highlight the enormous challenges that a community faces in meeting its minimum energy needs through traditional food harvesting. They suggest that if harvesting cannot be increased, imported market foods can be an important part of the solution to avoid food insecurity. Local food procurement is increasingly being hailed as a promising strategy for tackling food security issues in Canada’s north.

the Wapekeka First Nation, explains his region’s hunting traditions to Dr Robidoux.

Moving ahead

Given the diversity of Indigenous groups and the distinct geographies in which they live, it is vital to apply this analytical approach and research to all regions that engage in traditional food procurement to fully comprehend their potential influence on food security issues. The methods and analysis used here provide a repeatable model for evaluating land-based foods to determine their potential contribution to food security. Traditional cuisines are undeniably important in sustaining cultural continuity and resilience. As a result, while advocating for culturally relevant food policies that maximise local food sources is tempting, its capacity to effectively enhance regular access to nutritious food from the land remains unknown. To increase levels of food security in northern Canada, public (federal/provincial/territorial) expenditures in local food procurement require realistic evaluations of wild food availability and the factors that hinder and facilitate food access. However, the expenses of preserving traditional food practices must not be overlooked.

Robidoux and his research team are still working with northern isolated Indigenous communities to look into alternate funding models that might be self-determined and sustained through community economic growth, such as traditional food markets and professional hunting. The research presented here is a crucial first step for communities and governments in determining the amount of wild food required to supply even the most basic energy needs.

Do you have any specific suggestions for policymakers adapting your research to improve the situation of food insecurity in Canada?

Our research group has advocated for the public support of local food solutions in northern Indigenous communities for over a decade. Traditional food sources and drawing from the land means much more than just meeting nutritional needs, as they are critical for ensuring cultural continuity and resilience. Their potential contribution to helping address food security, however, needs to be better understood for policymakers looking to support local food procurement as a food security strategy. Public investment must acknowledge the unique challenges communities face and must work with communities to move forward within the contemporary social and economic context.

References

- Robidoux, MA, Winnepetonga, D, Santosa, S, Haman, F, (2021) Assessing the contribution of traditional foods to food security for the Wapekeka First Nation of Canada. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme, 46(10), 1170–1178. doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0951

- Loukes, KA, Ferreira, C, Gaudet, JC, Robidoux, MA, (2021) Can selling traditional food increase food sovereignty for First Nations in northwestern Ontario (Canada)? Food and Foodways, 29(2), 157–183. doi.org/10.1080/07409710.2021.1901385

- Robidoux, MA, Mason, CW (eds) (2017) A land not forgotten: Indigenous food security and land-based practices in Northern Ontario. University of Manitoba Press, 221–223. ISBN-10: 9780887557576, ISBN-13: 978-0887557576

- Imbeault, P, Haman, F, Blais, JM, et al, (2011) Obesity and type 2 diabetes prevalence in adults from two remote first nations communities in northwestern ontario, Canada. Journal of obesity, 267509. doi.org/10.1155/2011/267509

10.26904/RF-139-2027803305

Research Objectives

Together with an interdisciplinary team, Dr Robidoux studies the contribution of traditional foods to food security in northern isolated communities.

Funding

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

Collaborators

- Derek Winnepetonga, Wapekeka First Nation

- Dr Sylvia Santosa, Concordia University

- Dr François Haman, University of Ottawa

Bio

Dr Michael Robidoux is a Full Professor and Director and Associate Dean of the School of Human Kinetics, Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Ottawa. With expertise in the field of ethnology, Dr Robidoux has led multidisciplinary research programmes studying land-based food practices in rural remote Indigenous communities in northern Canada for over twenty years. Dr Robidoux and his Indigenous Health Research Group have developed longstanding partnerships with Tribal Organisations and Indigenous communities, advocating to build local food systems in northern Canada to address high rates of food insecurity and the disproportionately high prevalence of dietary-related disease. He is particularly interested in studying the impact of local food procurement on local dietary practices and developing economic strategies to help build local food capacity in remote northern communities.

Contact

University of Ottawa

125 University Street

Ottawa, Ontario, K1N6N5

Canada

E: robidoux@uottawa.ca

T: +1 613 240 0529

W: indigenoushealth-santeindigene.ca