- Museums give us a chance to see history from new perspectives and to meaningfully reflect on the past.

- Dr Silke Ackermann, Director of the History of Science Museum at the University of Oxford, UK, is an expert in the transfer of knowledge between Europe and the Islamic world.

- She believes that we should transform museums to make them inclusive and engaging for everyone.

- Ackermann invites us to question the world around us and to discover what objects of the past can tell us about humanity today.

When Dr Silke Ackermann began studying medieval history, she had no idea how exciting and thought-provoking it might be. Through her own studies, she discovered the joy of interrogating the past through the tactility of historical artefacts and manuscripts themselves. Now, as the first female Director of the History of Science Museum at the University of Oxford, UK, Ackermann looks to pass this approach on, engaging students and the public both in the museum and abroad.

In this enlightening interview with Research Features, she tells us about the Vision 24 project, keeping museums relevant in a modern world, and why she thinks every one of us needs to stay in touch with our past.

How did you become interested in the field of medieval and early modern science?

By complete chance! I started off studying contemporary history. I moved onto classical history and left the Middle Ages out because in Germany, where I studied, it was taught only very rudimentarily in school and didn’t seem interesting. Then, in later years, I discovered that there was a perfect link between European medieval studies and sources from the Islamic world, which had been little researched; this was just the perfect combination.

I had one professor at the time who was brilliant at storytelling. The Middle Ages on the surface did not seem very exciting, but he managed to make it so. What’s more, another colleague – one of the few women in the department – also managed to bring her topic to life in a way which I thought was just mind boggling, and this really inspired me. The whole world was opening up for me, and this is why I’m such a strong proponent for storytelling and interaction. That is why we are so privileged in museums, because we have so much interaction with the public. You do cutting-edge research, and at the same time you have an opportunity to share with everybody what gets you out of bed in the morning and make that research accessible to all on a huge range of levels, from PhD students to young children.

How do you see museums and culture inspiring future generations?

As part of our major transformation project, Vision 2024, we have changed our mission ‘To explore the connections between people, science, art, and belief.’ In other words: to create a meeting point in every sense of the word.

We need to support and inspire academic colleagues to feel confident using objects and material culture for teaching and research.

Firstly, a place where people can meet physically. At the History of Science Museum we have lots of entrances, but not one of them is step-free. I passionately believe that what we need is not ‘just’ access, not just a lift somewhere in a corner, but full inclusion. Full inclusion means that everybody, whatever their background or mobility, can come into the museum feeling welcome.

The second element is about making the objects intellectually accessible, to empower visitors to explore history from diverse angles: ‘I haven’t got a clue how that object works, but I find it really beautiful!’ That’s perfectly alright because that’s what many people who made them, collected them or commissioned them thought, too.

This inclusive project is important because in the increasing specialisation of the past centuries we have constantly been made to choose: are you an ‘artist’ or a ‘scientist’? We have lost sight of what humanity is really about and the overlaps between otherwise compartmentalised ‘specialisms.’ The term ‘science’ is so misleading. The German term ‘Wissenschaft,’ which refers to ‘science’ broadly and the sharing of knowledge, or the Arabic term ‘ilm,’ to have knowledge of something, are much more suitable. The Latin term ‘scientia’ which is where the word ‘science’ comes from, also means ‘knowledge’ – a meaning that is now widely forgotten. I prefer to talk about knowledge transfer, and believe ‘science’ at the museum should be much more inclusive in every sense.

What inspired you to work in your research field and museums?

When I was writing my PhD on 13th century mathematician, astronomer and astrologer, Michael Scot, all his works were in manuscript form. When you touch a manuscript from that time it really is a spine-tingling thing.

The person who wrote this was a monk sitting in some monastery 700 years ago! It’s something a printed book can never give you, that immediate connection to that other human. We need to support and inspire academic colleagues to feel confident using objects and material culture for teaching and research to share, and pass on this thrill to the next generation.

I found that while I studied I’d never heard of the topics Michael Scot was exploring, like astrolabes, for example. I went back to where I was studying in Frankfurt/Main to the Institute for the History of Science, led by David King. He allowed me to sit in on the sessions and after showing a keen interest, he offered me a role as an assistant, despite my struggling so much at the time to try to understand what was going on.

You are the first female head of a museum in Oxford. Did you encounter many challenges getting involved in museums and culture?

There are far more women in museums than men, but there are far fewer women in the senior leadership positions. It would be a lie to say that I don’t get a lot of patronising comments; you just have to learn to deal with that.

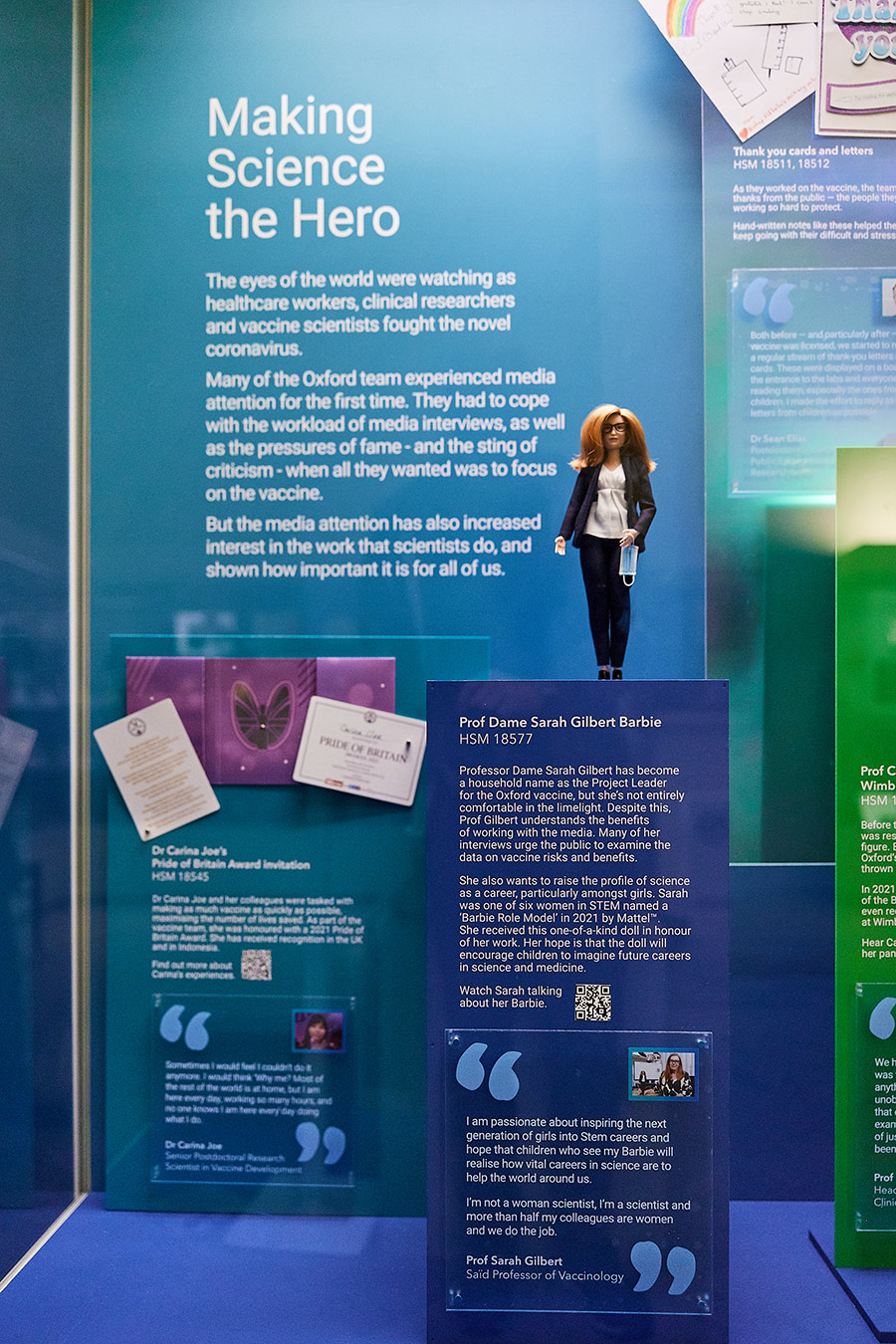

The fact that I was the first female head of the museum is so often brought up when we have an event at the museum, and I always get a round of applause. That is very nice, of course, but I hope that one day that fact won’t even be worth mentioning anymore. In our current exhibition, there is a display around COVID-19 and Sarah Gilbert is very prominent in that. She’s often framed in the media as a ‘woman scientist,’ but I heard her say ‘I’m not a woman scientist, I’m a scientist who happens to be a woman!’

Do you think there should be outreach requirements for academics in receipt of funding?

Funding is one of the major challenges we face in museums. Colleagues who work entirely in an academic department find that we are a drain on resources, but we as museums and collections are the window to the outside world for most people’s research. One colleague who started with us on a project expected that an exhibition was just lots of text on a wall. But, as a result of us working together, they now say that they’ve learned there’s a very different engagement – public engagement – which is really useful for their funding applications.

There are now many funding bodies that ask for ‘impact’: It’s great you’re doing this fantastic research, but how is this going to impact society? How is this impacting groups around you? I think this is exactly what we should be doing, especially when funding is so scarce. I’ve had heated debates at many formal dinners with colleagues who are adamant that they should get the funding regardless, and I keep making the point, ‘You know your funding could go to a hospital or school, please explain to me why you should get it.’

Only if we take our cultural heritage seriously and understand where we are coming from do we have a future. But if we don’t make museums or the engagement with the past more relevant for everybody, nobody’s going to support investment.

Can you tell me a bit more about knowledge transfer and active learning?

My style is to say, ‘Okay we’re going to discuss this topic. So, tell me what you know about this!’ before I start ‘lecturing’ so that the students can take an active part. I always learn from those engagements and they can lead into completely unexpected directions. Somebody may ask me a question and I think ‘Gosh – not only do I not have the answer, I’ve also never even thought about this!’ That’s fantastic!

Only if society takes its cultural heritage seriously and invests in it, do we have a future!

An object can also invite you to explore your preconceptions. Take a swastika, for example. Our generation immediately thinks of Nazis. But the swastika is a symbol much older than that.

A trident is often associated with the devil, but can also be the three-pronged spear that the Greek god Poseidon is frequently depicted with. This is to say: ‘Park what you think you know, and look as if it was the first time! What do we see?’ When you look at the same object as I do, your narrative may be totally different from mine.

I get very excited about all sorts of projects we are doing here; The Star of Bethlehem: Journey through Science and Art is a joint project with a colleague from the USA. It’s very much the epitome of what we’ve been talking about. You see the star on Christmas wrapping paper, mostly as a comet. But what was it? Where is it coming from? What are the origins, what is its parallel with other religions? How is it depicted? And why? Interactive, reflexive, curiosity-driven learning should be at the heart of museums and culture and the research landscape as a whole.

Interview conducted by Todd Beanlands todd@researchfeatures.com