- Modern mental health services fail to effectively cater for migrant Pacific Island communities, which have different worldviews and ways of knowing.

- At the University of Waikato, Associate Professor Sione Vaka has developed the ūloa model of care, which draws inspiration from traditional research methods and ways of life.

- The ūloa model offers Pacific-centred mental health services with cultural appropriateness and equitable outcomes.

Migrant Pacific peoples experience higher rates of mental illness compared with those in the general population (25% vs 20% in Aotearoa/New Zealand). At the same time, Pacific Islanders have poorer access to mental health services. These disparities reflect cultural and language barriers, stress of adapting to a new environments, and socioeconomic challenges.

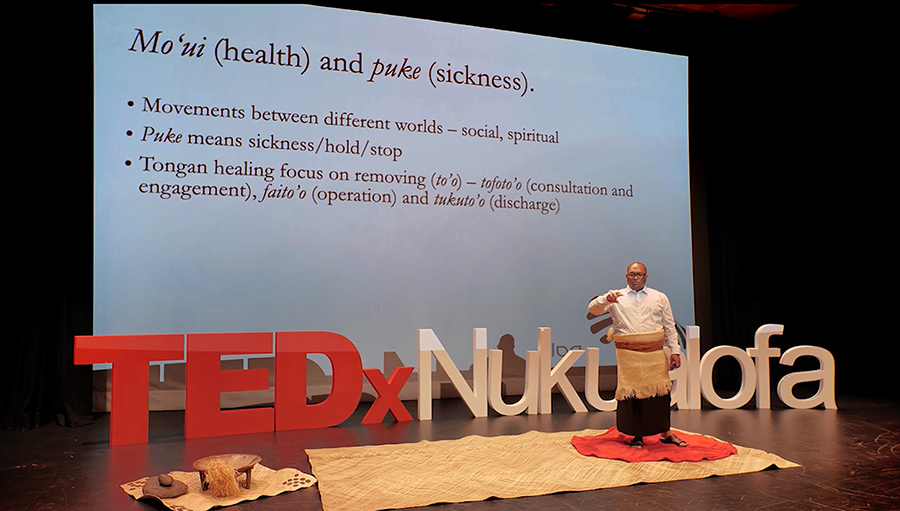

In addition, the very way in which mental health and illness are understood differ markedly between Western-centric medical paradigms and Pacific island communities. For instance, in the Cook Islands, the word for health, ora‘aga, encompasses all of a person’s social relationships, along with their physical, spiritual, and emotional relationship with the environment; a person is at peace (or ‘healthy’) when all of these relationships are in balance. Similar connections between human health and the natural environment are found in Māori and Aboriginal perspectives of health.

The Western-centric medical provision is individualised and linear focused which misses the collective and cultural focus of the Pacific worldviews. Ūloa captures all these worldviews.

In Aotearoa/New Zealand, initiatives are in place to better prepare mental health service providers working with Pacific people; what is more, some specialist services combine approaches from Western medicine with those from traditional healing. However, mental health services still struggle to effectively address the unique needs of Pacific communities, necessitating a shift towards more culturally appropriate models of care. At the University of Waikato, Associate Professor Sione Vaka, with support from the Health Research Council, is seeking to develop a Pacific-centred model for mental healthcare, ūloa, which is rooted in talanoa, a traditional Pacific research approach.

Talanoa: an alternative research methodology

Academic research is largely centred on the hypothetico-deductive approach, which emphasises objectivity and hypothesis-testing using quantitative and qualitative methods. However, this approach is often at odds with traditional ways of knowing practiced by Indigenous communities.

Talanoa is a research method that can capture Pacific worldviews, ways of communication, cultural values, and philosophies. Talanoa, a term understood across Pacific nations, is simply defined as ‘talking’; however, the concept is nuanced, aiming to capture the ‘who, what, where, how, and why’.

In practical terms, talanoa is practiced in groups, both formal and informal, where participants use storytelling and personal experiences/histories to explore topics from different perspectives and work towards consensus (noa). Taking the ‘coconut’ as an example; during talanoa, one individual might describes the parts of a coconut tree (trunk, leaves, fruit), another the role of that tree within the ecosystem; one might focus on the separate parts of the fruit (husk, flesh, milk) and their uses, another on the role of coconuts in socio-economic structures. The sum of the parts is comprehensive knowledge of the physical, social, and geographical features of the coconut.

Everyone plays a part and they all work together – the fish are distributed throughout the community. Please note that they are shared equally according to their roles, responsibilities, and ranks in the society.

Talanoa is particularly effective in Pacific research contexts because it allows for a personal and relational approach to data collection, which aligns with the communal and relational nature of Pacific societies.

Ūloa: A mental healthcare model for Pacific people

The Tongan concept of ūloa proposes that all fish caught within a community are shared equally by that community. Each fisherman constructs a coconut leaf net (au) on instruction from a toutai (lead fisherman). The fishermen hold on to each other, creating a single large net from the sum of the smaller au. Together they move forward, collecting fish in a sack.

In the ūloa model proposed by Associate Professor Vaka, fish represent mental health service users, the toutai is the mental health worker, each au is a family or other relevant stakeholder, and the collective net is the community. The ties that bind the au are determined through talanoa, which provides open and clear communication from all perspectives within safe spaces (eg, homes) for the service users, their family/community, and healthcare providers.

In fishing communities and mental healthcare settings alike, four main steps are critical:

(1) Tufunga (construction): carefully planning how the ’fishing day’ (or provision of mental health services) will proceed. The talanoa process is led by the toutai, who consults with community elders/experts and the community to determine the time, place, scope, and other practical considerations.

In Tongan culture, there are three broad underlying concepts for mental distress; identifying the relevance of each during the tufunga stage is crucial: tufunga faka-Tonga (curses and possession by spirits), tufunga fepaki (socioeconomic issues such as migration, social networks, resources and services), and tufunga faka- paiōsaikosōsiolo (physiological issues, such as those associated with stress, substance abuse, and mental disorders).

(2) Toutai (fishing): during the fishing process, the toutai directs operations, ensuring that all parts of the net move in harmony and that connections between individuals are strong. In a mental healthcare setting, the toutai manages all the connection points in the treatment programme (eg, traditional healers, doctors, mental health services, family, community), harnessing the unique skills and knowledge of each to ensure the best possible care outcomes for service users.

(3) Tufa (distribution): when fishing is complete, fish are distributed within the community; none are sold for profit, and cheating brings great shame. Through this process, the community stays strong and united. Within a mental health service, this step involves the positive outcomes of the mental health service being felt back within the community.

(4) Tofu (peace and harmony): successful ūloa results in peace and harmony, be it within a traditional Tongan fishing community or modern community facing a 20th century struggle with mental health issues.

By weaving cultural elements into the fabric of mental health services, the ūloa system offers more accessible, meaningful, and effective healthcare to Pacific Island communities.

Has the ūloa model been tested in a clinical setting? If so, what were the outcomes?

The ūloa has been tested in Auckland. The study findings continue to support that the conventional biomedical approach employed in the mental health services overlooks elements of Tongan constructions of mental illness and the intersections between Tongan and biopsychosocial themes. Care that is based only on the ‘medicine’ rather than bringing the spiritual aspect into care planning (fake leaves) will not serve the needs of the Tongan community.