Cyst infection is a common and serious complication of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, which can be difficult to treat and sometimes fatal. However, much is still unknown about this complication. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) is usually recommended for detecting cyst infections, yet its drawbacks include limited availability, high cost, and radiation exposure. Therefore, Dr Tatsuya Suwabe’s team at Toranomon Hospital devised diagnostic criteria for using the more widely available magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). They also conducted a review of antibiotic therapy protocols, and made recommendations for further research, including investigating the association between the microbiome and cyst infection.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is a common, inherited type of kidney disease. Of those living with the condition, an estimated 30-50% experience kidney infection at some point in their lifetime, and 9% have infections so severe as to require hospitalisation. These serious cases can be resistant to antibiotic treatment and some are fatal. Despite the understood gravity of this condition, there is a gap in our knowledge of cyst infection in ADPKD and a lack of evidence-based guidelines for managing the issue.

Recognising this gap, Dr Tatsuya Suwabe and his team conducted a study of kidney patients at Toranomon Hospital in Japan, with the aim of reviewing the evidence surrounding diagnostics and therapeutics. Here, we take a closer look at their findings regarding diagnosis, antibiotic therapy, cyst drainage, transcatheter arterial embolisation (TAE), and the role of intestinal flora.

Cyst infection in ADPKD: Diagnosis

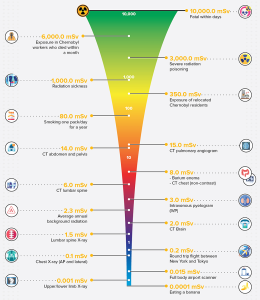

The study discussed two types of medical imaging that may be used to diagnose cyst infection in ADPKD patients. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) is currently recommended for detecting infected cysts. However, disadvantages to this method include its limited availability, high cost, and increased radiation exposure. Another disadvantage specific to the studied population is that PET-CT is not covered by medical insurance in Japan, unlike MRI.

Additionally, as of 2017, Japan had 50 MRI scanners per million population, as opposed to 5 PET-CT scanners per million, making MRI far more widely available. However, there are some drawbacks associated with using MRI. Firstly, MRI is less specific than PET-CT, which can make it difficult to differentiate between an infected kidney cyst and a haemorrhage inside the cyst. Nevertheless, as the majority of the study participants had undergone renal TAE – a procedure which can shrink an enlarged kidney by up to 45% on average and reduces the likelihood of this type of haemorrhaging – MRI was more likely to result in an accurate diagnosis of infection than it may have been among other populations.

“Administering fluoroquinolones as a blanket policy for cyst infections in ADPKD should be reviewed due to the risk of overuse.”

The researchers defined four criteria for diagnosing cyst infection in ADPKD by MRI. These include:

- a high signal intensity (SI) on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI);

- fluid-fluid level;

- wall thickening;

- gas.

They concluded that it was possible to identify most cases of severe cyst infection in need of drainage by applying these four MRI criteria along with abdominal pain at the same location, changes from previous MRI results, and a cyst diameter of more than 5cm, with almost 100% sensitivity and at least 84.4% specificity.

Antibiotic therapy for infected cysts

Lipid-soluble antibiotics are recommended to treat infected cysts in ADPKD as they penetrate the cyst wall more effectively than water-soluble antibiotics. Of the lipid-soluble antibiotics, fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole are the most effective against bacteria such as E.coli, which is the main causative agent in cyst infection in ADPKD. Unfortunately, however fluoroquinolone-resistant microorganisms are commonly found in infected cysts. Therefore, treatment with the water-soluble antibiotic, carbapenem may be necessary in some cases where the cyst infection is resistant to lipid-soluble antibiotics.

As little was known about the penetration of carbapenems into infected cysts in ADPKD, the authors carried out an investigation and found that penetration was poor. However, MEPM (Meropenem) is known to be an effective treatment for infected cysts in most ADPKD patients. This might be because most bacteria have a relatively low minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), meaning the lowest concentration of an antibiotic needed to prevent the growth of a microorganism. As the MIC of MEPM is high for other bacteria, this may explain why MEPM is not always effective in treating infected cysts.

It is accepted practice to perform blood cultures before administering antibiotics. However, where the causative microorganisms cannot be identified, fluoroquinolones may be used. Nevertheless, the findings suggested that administering fluoroquinolones as a blanket policy for cyst infections in ADPKD should be reviewed due to the risk of overuse. In the case of severe cyst infections, water-soluble antibiotics, such as carbapenem, may not be effective and, therefore, fluoroquinolones should be given. However, if the cyst infection is mild, water-soluble antibiotics should be administered, to prevent abuse of fluoroquinolones.

While definitions of severe and mild infection remain controversial, Dr Suwabe suggests several factors for physicians to consider when determining severity. These include the patient’s general condition, including blood pressure and body temperature, clinical history, laboratory test results (including white blood cell count and serum C-Reactive Protein), and imaging features of infected cysts. Where sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) are present, infection should be considered severe.

Antibiotic therapy should be continued until the symptoms have completely improved, taking into account the drug half-life, as sustaining the level of antibiotics inside the cyst may depend on its serum concentration being sustained.

Drainage of infected cysts

Where the infection is resistant to antibiotics, drainage of the cyst may be considered, taking into account the risk of severe adverse events. Dr Suwabe’s suggested criteria for cyst drainage in case of infection includes: 1) where the infection is resistant to antibiotics (with a fever lasting for 1–2 weeks despite administration of appropriate antimicrobials); 2) where the diameter of the infected cyst exceeds 5cm; 3) where the infection is severe (such as in the presence of sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), etc.); and 4) in cases of recurrent cyst infection.

The study notes the importance of continuing to explore the best surgical procedures and optimal timing for cyst drainage. This is because performing the procedure when a patient is in a poor condition may worsen their condition and lead to fatality due to the invasive nature of surgery. It is better to wait until the patient begins to show improvement in their overall condition. However, it must also be borne in mind that some patients do not respond to antibiotics, in which case cyst drainage must be carried out quickly.

“The authors hypothesised that renal transarterial embolisation (TAE) may prevent renal cyst infection in ADPKD.”

Transcatheter arterial embolisation

As the infection of kidney cysts is believed to be caused by the spread of bacteria through the blood, the authors hypothesised that renal transarterial embolisation (TAE) may prevent renal cyst infection in ADPKD. This is due to the cutting off the blood supply, and therefore the spread of bacteria, by blocking the renal arteries. However, in some patients the blood supply and the urine are not shut off completely and therefore infection is still possible.

Shutting off the blood supply to the kidney may also have a negative effect if infection is present when renal TAE is performed. This is because the blood supply is also the route by which antibiotic treatment is delivered. If the blood supply is blocked, so too is the vehicle for the treatment. However, renal TAE appears to be more successful at preventing infection than hepatic (liver) TAE. This may be because the arteries of the liver are only partially blocked in hepatic TAE. The authors concluded that further research is needed to determine the effect of TAE on cyst infection in ADPKD patients.

Cyst infection and the microbiome

As enterobacteria (the group of bacteria to which E-coli belongs) are among the main causative bacteria in cyst infections, the microbiome may play a key role, by working with the innate immune system to ward off bacterial infection. Dr Suwabe suggests that as intestinal probiotic bacteria are not causative bacteria of cyst infection and probiotics have been shown to be effective for colitis, they may have a role to play in preventing cyst infection. In particular, specific strains of lactobacillus may influence the host immune system by promoting production of the antibody immunoglobulin A (IgA).

Having provided recommendations regarding diagnostic criteria and antibiotic therapy for infected cysts arising from ADPKD, Dr Suwabe highlights key areas requiring further research, including the role of intestinal flora and nutritional status in cyst infection, the role TAE may play in preventing cyst infection, and the association between antibiotic half-life and its effectiveness in treating cyst infection.

What is next for your research?

Our next objectives are to verify our new antibiotic strategy for cyst infection in ADPKD and to establish the best surgical procedure and optimal timing for cyst drainage. In addition, we’ll explore the role of intestinal microbiome on cyst infection and verify the preventive effect of renal TAE for renal cyst infection.

References

- Suwabe, T. (2020). Cyst infection in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: our experience at Toranomon Hospital and future issues. Clinical and Experimental Nephrology, [online] 24, pp 748–761. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10157-020-01928-2

- Suwabe, T et al (2016). Intracystic magnetic resonance imaging in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: features of severe cyst infection in a case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 17:170. DOI:10.1186/s12882-016-0381-9

- Suwabe, T et al (2016). Suitability of Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease for Renal Transcatheter Arterial Embolization. J Am Soc Nephrol. 27(7) pp 2177–87. DOI:10.1681/ASN.2015010067

- Suwabe, T et al (2015). Cyst infection in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: causative microorganisms and susceptibility to lipid-soluble antibiotics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 34 pp 1369–79. DOI:10.1007/s10096-015-2361-6

- Suwabe, T et al (2012). Clinical features of cyst infection and hemorrhage in ADPKD: new diagnostic criteria. Clin Experim Nephrol. 16 pp 892–902. DOI:10.1007/s10157-012-0650-2

- Suwabe, T et al (2009). Infected hepatic and renal cysts: differential impact on outcome in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 112(3) pp 157–63. DOI:10.1159/000214211

10.26904/RF-137-1592197600

Research Objectives

Dr Tatsuya Suwabe’s research explores improved treatment and care for patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

Funding

- Okinaka Memorial Institute for Medical Research, Toranomon Hospital

- JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K17758

- Grant-in-Aid for Progressive Renal Disease Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan

Collaborators

Yoshifumi Ubara (former manager, Department of Nephrology, Toranomon Hospital)

Bio

Dr Tatsuya Suwabe is Chief Physician, Department of Nephrology, Toranomon Hospital. He has 20 years of experience in Nephrology and has performed over 1,000 cyst drainage procedures and over 700 renal transcatheter arterial embolisation procedures in patients with ADPKD. Dr Suwabe carried out clinical research in ADPKD in Mayo Clinic, MN and obtained a Master of Science in Mayo Clinic Graduate School in 2018.

Contact

Address Tatsuya Suwabe

Department of Nephrology, Toranomon Hospital Kajigaya,

1-3-1 Kajigaya Takatsu-ku Kawasaki Kanagawa 213-8587 Japan

E: suwabetat@gmail.com

T: +81-44-877-5111

W: https://toranomon.kkr.or.jp/global/